Two Views of the Wakarusa

- Robert Hagen

- Sep 22, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 23, 2025

Environmental work is not just about natural science. Solutions to environmental issues require collaboration across disciplines. It’s impossible to be an expert in all these areas, but we can learn enough to communicate with other people who are, and recognize what different fields contribute to the shared goal.

Since 2007, I’ve had the privilege of teaching field courses for the Environmental Studies Program at the University of Kansas (KU). I partially retired in August 2025, but continue to serve as Field Education Coordinator for the program, supporting new instructors and helping other faculty include outdoor activities in their classes. As I step away from actively teaching, I find myself reflecting on lessons I’ve learned as a student of environmental biology over the past 50 years.

My roots are in western Washington state. Growing up in what were then the sleepy suburbs of Seattle, my most significant experiences were outdoors: hiking, camping, exploring natural areas. I graduated from high school in 1971. After a couple of confused years as a chemistry major at a small college—then a year spent working on a golf course and hiking through California—I transferred to the University of Washington (UW) where I began taking courses in biology.

Fifty years ago, the UW didn’t have an undergraduate degree in ecology. That was a problem for me, because I wanted to take more botany classes than a zoology major would permit, and more zoology classes than a botany major. My personal solution was to major in “Cell and Molecular Biology,” which (despite the title) allowed me to enroll in the courses I wanted! (Had I been a student at KU in 1974, I could have chosen the new Environmental Studies major—one of the first interdisciplinary undergraduate programs in the country.)

I discovered as I continued my undergraduate education that I really enjoyed the university environment; I love the excitement and challenge of encountering new ideas. That led me to graduate school at Cornell, working in a research lab studying interactions between plants and the insects that eat them. I focused my graduate work on the evolution of the North American tiger swallowtail butterflies, which I continued for a few more years of post-doctoral research. In 1991, I moved to Lawrence with my wife—a spider and bee researcher—who joined the KU Entomology department faculty. I bounced around in a variety of teaching and research roles at KU before joining the Environmental Studies Program full-time.

The Environmental Studies Field Ecology course at KU was first taught in spring 1976, shortly after the program was established. The founding professors recognized that bringing students outdoors was essential to the new curriculum. All Environmental Studies majors take the course. I taught Field Ecology with other KU faculty for a couple of years in the mid-1990’s, then was the sole instructor from 2007-2024.

From the beginning, Field Ecology has included lab sessions on lakes, streams, prairies, woodlands, wildlife biology, and conservation—as much ecosystem diversity as we can fit into a semester. The students are also diverse—reflecting the interdisciplinary scope of the program. Because my academic background is firmly anchored in natural science—in particular, terrestrial ecology and evolutionary biology—I’ve appreciated the opportunity to expand my own knowledge and perspective. As all instructors discover, the best way to learn a subject is to teach it!

Two Views of the Wakarusa

My favorite definition of science is that it is “a way of knowing.” Science is a tool, amazingly useful for answering some kinds of questions, but useless for others. (It’s one way of knowing, not the only way!) Teaching in the Environmental Studies Program at KU has offered me the benefit of working with artists, poets, historians, experts on literature, social scientists, urban planners, and lawyers—along with natural scientists from diverse fields.

Students in the fall 2024 Field Ecology class were able to experience some of that diversity in knowing when we visited a section of the Wakarusa River near Lawrence, about 1 km downstream of Clinton Dam. The river upstream of this site is highly modified: water from the reservoir is released through concrete pipes and flows through a straight, rock-lined channel for most of the distance.

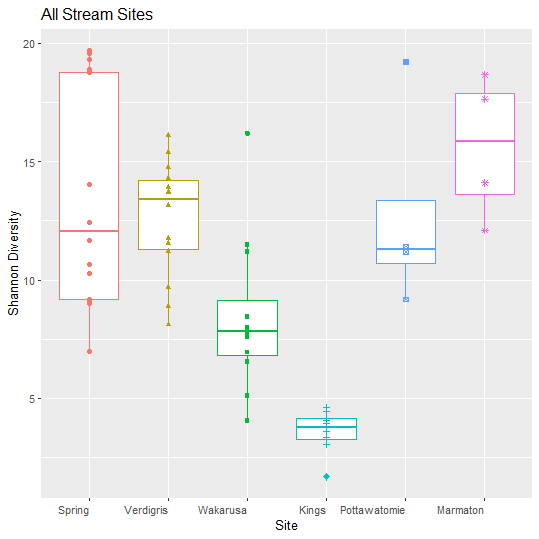

The goal was to introduce students to methods used for stream health assessment. At the Wakarusa site, they sampled stream aquatic macroinvertebrates. Later, they used taxonomic keys to identify organisms they collected and calculated measures of biodiversity. Students then compared their results with those obtained by classes in previous years, and with data collected by federal and state agency staff from “reference streams.” (Reference streams are those sites which represent the least human-disturbed habitats in a region; they provide a standard for categorizing stream health.)

By coincidence, at the same time, Rob Harper-O’Connor, a Lawrence-based artist, was at work on a painting of the site. Students had an opportunity to talk with Rob as he worked and explained some of what they were doing. I realized that we were also creating a portrait of the stream: Rob’s was composed of oil paint on canvas; ours would consist of data in a table. Creation of both portraits requires proficiency with tools, practice, and careful attention.

Those technical details are essential, but not sufficient. A successful portrait also requires a broader vision: purpose, intention, meaning or context. In the visual arts, that may be difficult (or impossible!) to translate into words. In environmental science, that can take the form of questions which motivate the study. For our stream lab, those were “How healthy is this section of the Wakarusa River?” and “Has the condition of the Wakarusa changed over time, based on these measures of stream health?”

For teachers, the challenge is to find a balance between helping students master the essential methods, while not losing sight of the context and purpose. It’s easy for beginners to get lost in the technical minutia: learning to apply paint to achieve a particular visual effect; learning how to use a taxonomic key or calculate a statistic. Rob’s painting provided a way for these students to pull back, briefly, from the details and consider the landscape as a whole. What does a painter see here? What aspects is the painter emphasizing?

In the end, both pictures can be used to tell stories about the Wakarusa at this location. Just as it takes practice to learn how to read graph, it can take practice to learn how to read a painting. In this case, one simple message communicated by both is that—despite its location just downstream of the massive disruption caused by Clinton dam—this section of the Wakarusa looks quite nice! Dialog between the two pictures raises other questions: Is there a connection between aquatic invertebrate biodiversity and beauty? Do features that create visual interest—for example, variety in color and shape—also promote invertebrate biodiversity in a stream?

Lessons

When we actively include different perspectives of the environment—seeing them not in competition, but as complementary—the whole experience is enriched. This is similar to the concept of “two-eyed seeing,” originally developed to improve the effectiveness of science education for Native American students. The core idea is that including both western natural science and traditional Indigenous knowledge in the curriculum improves student understanding. Two-eyed seeing also addresses a fundamental limitation of science. Science is an extraordinarily effective way to discover how the physical universe works, but is utterly useless as a guide to what any of it means, what we should do about it, or why we should care.

Environmental work is not just about natural science. Solutions to environmental issues require collaboration across disciplines. It’s impossible to be an expert in all these areas, but we can learn enough to communicate with other people who are, and recognize what different fields contribute to the shared goal.

Bob Hagen

Retired Environmental Studies Lecturer

The University of Kansas

Bob Hagen was recognized with the 2025 Excellence in Conservation and Environmental Education Award at the Annual Awards Celebration, hosted by KACEE.

I really enjoyed reading about Bob Hagen’s work connecting field science and interdisciplinary learning how he treats both data and narrative as portraits of meaning. It brought to mind times in my own path when I wrestled with self-presentation decisions, even wondering if I should hire a professional resume writer to better tell my story. But posts like this remind me that power lies in owning the process, not outsourcing voice.

This post about dedication and contribution reminded me how commitment matters in every profession, including research. Many healthcare professionals work hard on studies but face long publication timelines. Using a Fast Track Medical Manuscript Publication Service can really help them share important findings sooner by streamlining the review and submission process without compromising quality or accuracy.

I appreciate the recognition of Bob Hagen's dedication to environmental education and student success. His commitment to fostering a deeper understanding of environmental issues is commendable. Similarly, the other site offers comprehensive assistance across various subjects, including Online Marketing Class Help, aiming to support students in achieving academic excellence. Both platforms emphasize the importance of education and support in their respective fields, contributing positively to their communities.